Plantar Fasciitis

Summary

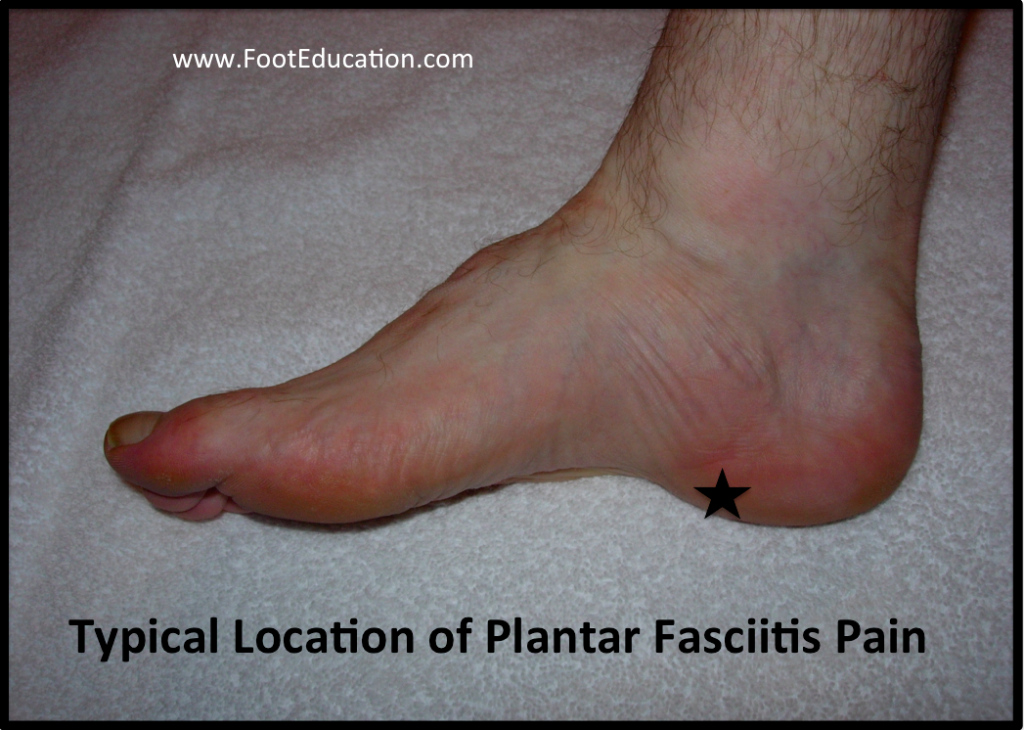

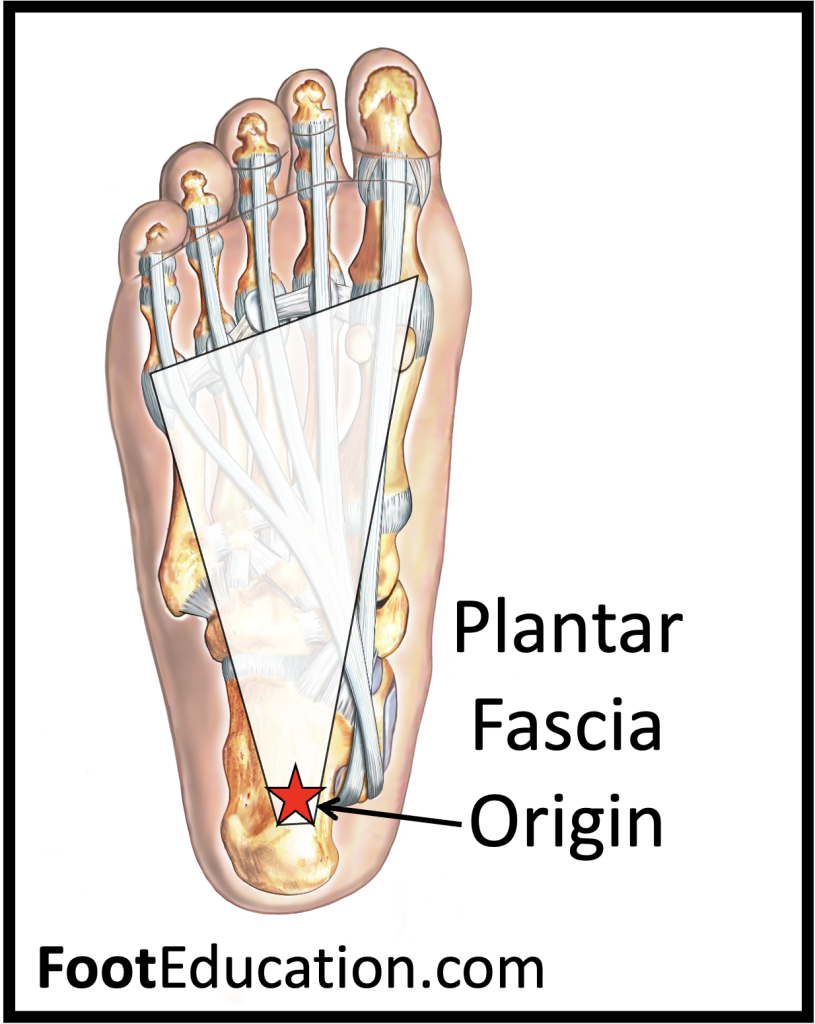

Plantar fasciitis is the most common cause of heel pain. The pain is typically located slightly in front of, and to the inside of, the fat part of the heel (Figure 1). Pain from plantar fasciitis is often most noticeable during the first few steps after getting out of bed in the morning. The plantar fascia is a thick band of tissue in the sole of the foot (Figure 2). Microtearing at the origin of the plantar fascia on the heel bone (calcaneus) can occur with repetitive loading. This microtearing leads to an inflammatory response (healing response) which produces the pain. Risk factors for plantar fasciitis include: excessive standing, increased body weight, increasing age, a change in activity level, and a stiff calf muscle. Plantar fasciitis can be managed non-operatively in the vast majority of patients. The main components of an effective non-operative treatment program are: calf stretching with the knee straight, plantar fascia stretching, activity modification (to avoid precipitating activities), and comfort shoe wear.

Patient Handout: Plantar Fasciitis

Clinical Presentation

Patients with plantar fasciitis almost universally give a history of pain with the first few steps in the morning. Pain is often also associated with first steps after periods of inactivity, such as sitting for lunch, or after getting out of a car. This pain is often located in the inside front part of the heel right where the plantar fascia originates (Figure 1). The pain can be sharp, but it will often improve after some movement or stretching. However, the heel pain will tend to recur as the day progresses, particularly if the patient has been doing significant weight-bearing activities, such as walking or standing. Burning pain is not typical of plantar fasciitis, and may suggest nerve irritation as a source of the pain (ex. Baxter’s neurtitis).

Plantar Fasciitis is associated with:

- Middle age

- A recent increase in activity level (ex. new running program)

- Jobs that require significant standing

- Increased weight

- Stiff calf muscles

Clinical examination will often localize the pain to the plantar medial heel region (Figures 1 & 2). Pain can also occur with direct pressure (palpation). There is often an associated stiffness (equinus contracture) of the calf demonstrated with the knee straight. Symptoms may also be exacerbated by placing the toes in a dorsiflexed position, thereby stretching the plantar fascia. There is an association between flatfeet and the development of plantar fasciitis. However, any foot type can develop this condition.

Plantar fasciitis is by far the most common cause of heel pain. However, there are other less common causes including:

- Overload heel pain syndrome

- Heel pad atrophy

- Entrapment of the first branch of the lateral plantar nerve (Baxter’s nerve)

- Tarsal tunnel syndrome

- Calcaneal stress fracture

- Periosteal inflammation

- Seronegative arthritis-induced inflammation

Imaging Studies

Plantar fasciitis is typically diagnosed based on the patient’s history and on physical examination. Plain x-rays are not routinely indicated. However, when ordered, a lateral, weight-bearing view of the foot will often demonstrate a calcaneal heel spur. Essentially, the same traction phenomena that causes overloading of the plantar fascia and its origin may cause excessive bone formation, in the form of a calcaneal heel spur. However, the presence of a heel spur does NOT directly correlate with symptoms. Many patients have heel spurs on x-rays and are asymptomatic, whereas, many patients have significant plantar fasciitis and do not demonstrate a heel spur on plain x-ray.

An MRI is initially not indicated for patients with heel pain that is believed to be secondary to plantar fasciitis. However, if symptoms fail to resolve after a concerted treatment effort, an MRI may be ordered to rule out other causes of heel pain, such as a calcaneal stress fracture.

Treatment

Non-Operative Treatment

There is excellent non-operative treatment available for plantar fasciitis. The vast majority of patients will have their symptoms resolve with non-operative treatment. The main elements of non-operative treatment are as follows:

- Calf Stretching (Figure 3): Regular daily calf stretching performed over a 6 to 8-week period will alleviate plantar fasciitis in almost 90% of patients. The stretching should be performed for a total of 3 minutes per day. It should be done with the knee straight so that the gastrocnemius is stretched, as this is the muscle that is tight. It should be performed on both sides. Six sets of 30 seconds per side is one method of achieving this. It is important that the stretch be done daily.

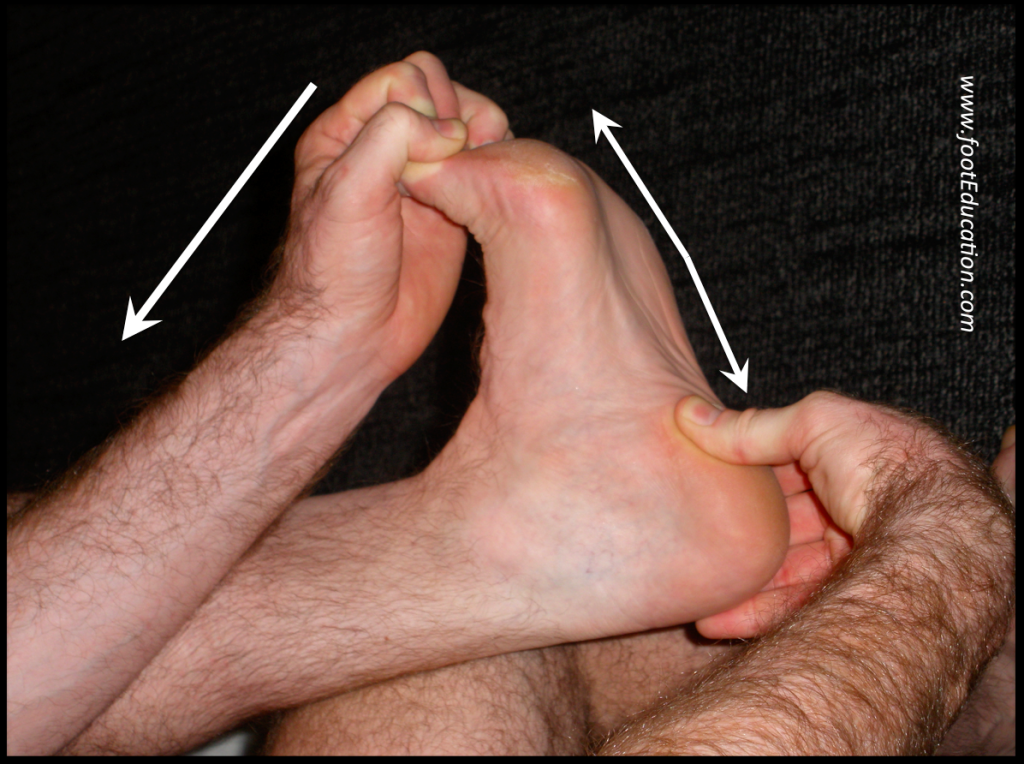

- Plantar Fascia Specific Stretch (Figure 4): Equally good results can be obtained with a formal plantar fascia stretch. Plantar fascia specific stretching has been found to provide symptomatic relief for the majority of patients. This is done in a seated position, and includes crossing the affected leg over the other leg. Using the hand on your affected side, take hold of your affected foot and pull your toes back towards your shin (Figure 3). This creates tension/stretch in the arch of the foot/plantar fascia. Check for the appropriate stretch position by gently rubbing the thumb of your unaffected side from left to right over the arch of the affected foot. The plantar fascia should feel firm, like a guitar string. The stretch position should be held for 10 seconds and repeated 10 times. The timing of when this is performed is important. It should be done prior to the first step in the morning and during the day before standing after prolonged inactivity. Most patients perform the stretch 4-5 times during the day for the first month, and then on a semi-regular basis (3-4 times per week). Decreased pain, with improvement of about 25-50% is expected at 6 weeks, with resolution of symptoms over 3-6 months.

With resolution of the heel pain symptoms, it is important to continue calf stretching and plantar fascia stretching on a semi-regular basis (3-4 times per week), so as to minimize the risk of recurrence. These treatment modalities treat the symptoms, but do not fully address the underlying biomechanical predisposing factors. Therefore, ongoing management of this condition is essential!

- Over-the-counter Orthotics. A soft, over-the-counter orthotic (Prefabricated orthotic) with an accommodating arch support has proven to be quite helpful in the management of plantar fascia symptoms. Studies demonstrate that it is NOT necessary to obtain a custom orthotic for the treatment of this problem.

- Comfort Shoes. Shoes with a stiff sole, a rocker-bottom contour, and a comfortable leather upper, combined with an over-the-counter orthotic or a padded heel can be very helpful in the treatment of plantar fasciitis.

- Anti-Inflammatory Medication (NSAIDs): A short course of over-the-counter anti-inflammatory medications may be helpful in managing plantar fasciitis symptoms, providing the patient does not have any contraindications, such as a history of stomach ulcers.

- Activity Modification Any activity that has recently been started, such as a new running routine or a new exercise at the gym, that may have increased loading through the heel area, should be stopped on a temporary basis until the symptoms have resolved. At that point, these activities can be gradually started again. Also, any activity changes (ex. sitting more) that will limit the amount of time a patient is on their feet each day may be helpful.

- Plantar Fascia Night Splint (Figure 5): A night splint, which keeps the ankle in a neutral position (right angle) while the patient sleeps, can be very helpful in alleviating the significant morning symptoms. A night splint may be prescribed by your physician. Alternatively, it can be ordered online or even obtained in some medical supply stores. This splint is worn nightly for 1-3 weeks, until the cycle of pain is broken. Furthermore, this splinting can be reinstituted for a short period of time if symptoms recur.

- Kinesiology Tape (KT Tape): When applied appropriately KT tape can provide excellent short-term relief of pain. However, the effect is lost when the tape is removed, and its effect tends to diminish over time. KT tape can be a helpful component of a coordinated approach to treating plantar fasciitis, especially during the early stages of the recovery.

- Weight Loss: If the patient is carrying significant extra weight, losing weight can be very helpful in improving the symptoms associated with plantar fasciitis. Essentially, anything that decreases the repetitive loading through the plantar fascia will help to alleviate the symptoms.

- Local Injection: For recalcitrant plantar fasciitis, some physicians will recommend a local injection of corticosteroids. This can be helpful in breaking the cycle of pain. Some physicians have advocated using PRP (Platelet-Rich Plasma) injections to treat recalcitrant plantar fasciitis. Unfortunately, these injections can be uncomfortable. There is also a very slight chance that they may lead to an infection. Furthermore, injections will not change the underlying biomechanics, so they typically need to be combined with the stretching protocols that have been previously described.

Operative Treatment

About 90% of patients will respond to appropriate non-operative treatment measures over a period of 3-6 months. Surgery is a treatment option for patients with persistent symptoms, but is NOT recommended unless a patient has failed a minimum of 6-9 months of appropriate non-operative treatment. There are a number of reasons why surgery is not immediately entertained, including:

- Non-operative treatment when performed appropriately has a high rate of success.

- Recovery from any foot surgery often takes longer than patients expect

- Complications following this type of surgery can and DO occur

- The surgery often does not fully address the underlying reason why the condition occurred, and therefore the surgery may not be completely effective.

- Prior to surgical intervention, it is important that the treating physician ensure that the correct diagnosis has been made. This seems self-evident, but there are other potential causes of heel pain.

Surgical intervention may include extracorporeal shock wave therapy or endoscopic or open partial plantar fasciectomy.

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy (High Energy): This is often performed under anesthesia. High-intensity shock waves are focused on the plantar fascia insertion. This creates a controlled injury to the plantar fascia. With the new blood supply entering this area as a healing response, the symptoms are often improved. There is a propensity for symptoms to gradually recur, although reasonable results have been reported at 6month and 2-year follow-ups.

Partial Plantar Fasciectomy: This involves removal of the injured area of the plantar fascia, either endoscopically or through the small incision. This is then followed by a 6-week period of relative rest and stretching. Although this procedure has produced good results, it can increase the risk of a rupture of the plantar fascia, with resulting profound flatfoot deformity and an increase in symptoms.

Gastrocnemius recession (a.k.a. Strayer or Volpious procedure): Recently, there have been a few studies which suggest that lengthening the calf muscle (gastrocnemius) can help resolve the symptoms associated with plantar fasciitis. This operation involves making an incision in the lower calf, in order to release the tendon of the gastrocnemius at the point where it inserts just above the Achilles tendon. Following the surgery, patients need a six week period of relative rest. The calf muscle can have noticeable residual weakness that usually resolves in 6-12 months. At this time, there are only limited studies assessing the long-term effectiveness of this procedure.

Click Here for a Summary Handout on Plantar Fasciitis

Edited by Stephen Pinney MD, previously edited by Jean Brilhaut, MD

Edited on April 5th, 2025