Navicular Stress Fractures

Listen to a Podcast on Navicular Stress Fractures

Summary

Navicular stress fractures are rare but serious injuries. They usually cause a dull ache in the middle of the foot, on top of the arch near the front of the ankle. These injuries are caused by repeated stress or pressure on the middle of the foot, often from high-impact sports or activities. Navicular stress fractures can be hard to diagnose because they may not show up on regular x-rays. Treatment usually includes staying off the foot completely for several weeks. If the fracture does not heal on its own, surgery may be needed to hold the bone together with screws.

Clinical Presentation

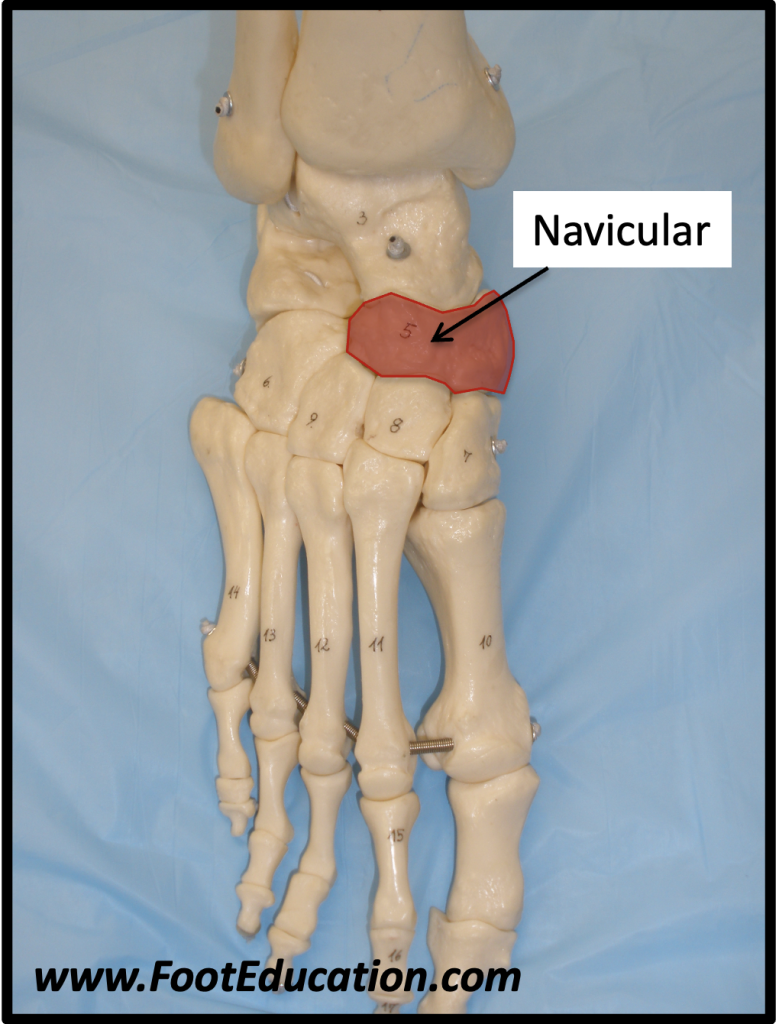

People with navicular stress fractures often feel a long-lasting ache in the middle of the foot (Figure 1). Anyone can get this injury, but it is most common in athletes. Unlike more common stress fractures in the forefoot (metatarsals), this injury usually happens from fast, repeated movements. Examples include the lead foot of a golfer, a middle-distance runner, or any athlete doing repetitive, high-impact actions.

Pain is usually felt in the middle of the foot and may not be in one exact spot, which can make this injury harder to diagnose. Pain may only happen during sports, but in some cases, people may limp even while walking.

Physical Examination

On exam, patients usually feel soreness when the doctor presses on the top of the middle foot. A careful doctor may be able to pinpoint the pain to the navicular bone itself. Trying to hop or rise up on the toes of the injured foot is usually painful. People with higher arches or a longer second toe may be at higher risk of this injury. These foot shapes may put more pressure on the navicular, especially during activities like sprinting and jumping that involve pushing off the toes.

Imaging Studies

X-rays often look normal, especially early on. Sometimes a faint fracture line can be seen. In more serious cases, or if the nearby joint is wearing down, x-rays will show changes. A diagnosis is usually made using an MRI, CT scan, or bone scan. MRI and CT scan also show whether the fracture goes all the way through the bone. MRI can also show if the bone has enough blood supply.

Treatment

These fractures are hard to treat because the navicular bone has a poor blood supply, and it absorbs a lot of force during walking and sports. If the fracture is not out of place, casting and staying off the foot for 6 weeks can work well. About 85–90% of people heal with this treatment. Some doctors may suggest a bone stimulator, which helps healing, although it may not speed things up.

If the patient puts weight on the foot too early, the chance of healing may drop to only 25%. Full recovery often takes three to four months or longer. For athletes, this injury usually ends their season. Sadly, some people may get the injury again, especially if the cause (like foot shape or activity level) doesn’t change.

Surgery may be needed if resting and casting do not work. Surgery usually includes drilling across the fracture and placing a screw or screws. In some patients a bone graft may be added to improve fracture healing. Surgery usually helps the bone heal, but recovery still requires rest and staying off the foot for several weeks.

Displaced Navicular Stress Fractures

In rare cases, the fracture may shift out of place. If this happens, surgery is needed to move the bone back into place, hold it with screws, and possibly add a bone graft.

Potential Complications of Navicular Stress Fractures

The main problem with non-surgical treatment is that the fracture may not heal, causing ongoing pain due to a “non-union.” If healing does not happen, further surgery may be needed.

Rarely, the navicular bone may collapse, which is very serious. If it collapses, it affects how the back of the foot works and is hard to treat.

If the fracture heals the wrong way, arthritis can develop in the nearby talonavicular joint. Surgery to fuse the affected joint can reduce pain but causes stiffness and needs a long recovery of six or more weeks without putting weight on the foot.

Edited by Stephen Pinney MD, October 24th 2025. Previously edited by Anthony Van Bergeyk, MD, Mark Perry, MD and Justin Greisberg, MD