Compartment Syndrome of the Lower Leg (Acute)

Summary

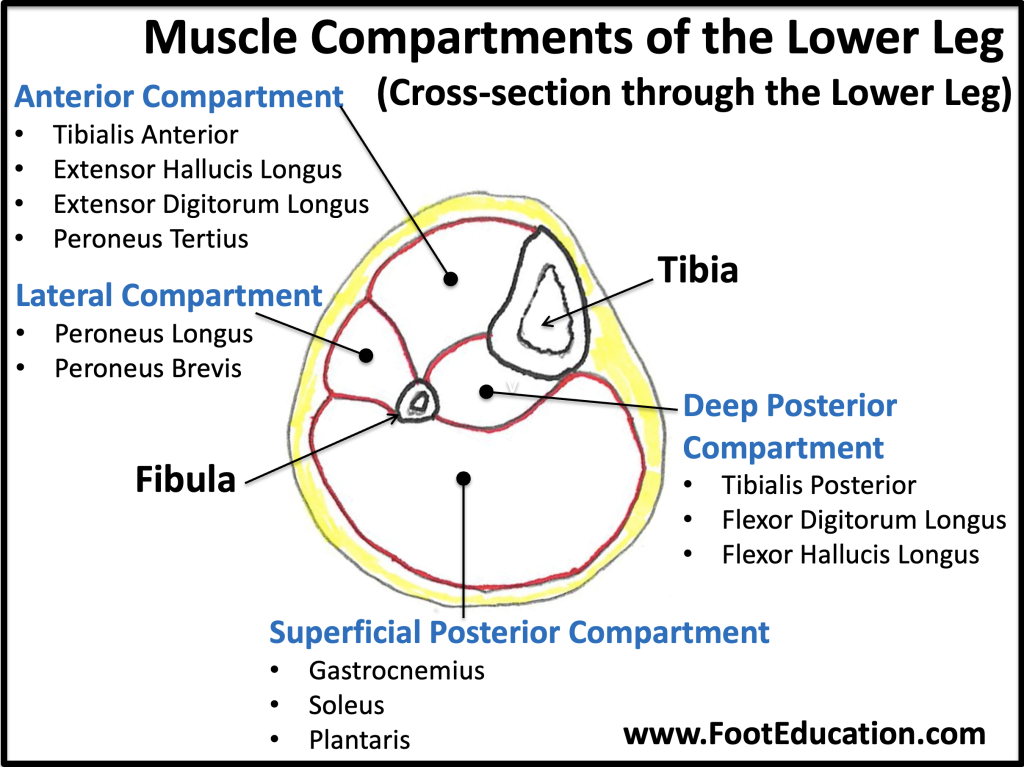

Compartment syndrome of the lower leg is a devastating condition that frequently leads to permanent muscle and nerve damage, which may be associated with lifelong disability. The muscles of the lower leg live in four “compartments” (Figure 1), regions of muscles enclosed by thick, fibrous sheaths. After a trauma such as a broken bone or a crush injury to the leg, the resultant bleeding or swelling increases the pressure in these compartments. When this pressure gets high enough, the veins in the leg get compressed and are unable to allow blood to exit from the leg. This congestion worsens the pressure in the compartments and prevents oxygenated blood from reaching the muscles of the leg, usually causing intense pain. If this situation is severe enough or lasts for too long (traditionally beyond six hours), the muscles in the leg can suffer irreversible damage and die, and nerves can suffer permanent injury. Treatment of an acute compartment syndrome is an urgent surgical release of the constricting fascia (fasciotomy) allowing blood flow and oxygenation to the muscles and nerves.

Clinical Presentation and Physical Examination

A typical scenario for the development of a lower leg compartment syndrome is a patient who suffered a high-energy trauma (ex. car accident, fall from a ladder) often associated with a tibia fracture, or other major injury. If there is excessive swelling the patient may develop intense pain in the leg after the injury or even after the broken bone is fixed surgically. In the hospital setting, patients with compartment syndrome usually complain of increased pain, and clinicians may find that patients who are developing compartment syndrome may require higher and higher doses of pain medication. Other findings such as pain with ankle motion, which can stretch the involved muscles, are also characteristic, but symptoms such as numbness due to nerve compression are generally late findings and should not be relied upon to make a diagnosis.

Serial examination, close observation, and clinical suspicion are essential to early diagnosis. There is not one single exam finding that definitely diagnoses compartment syndrome, so it should be considered in any patient who is at risk for the condition. Beyond increasing pain, patients who have pain with passive range of motion of the ankle or toes, firm compartments, numbness, or loss of pulses should be considered to have compartment syndrome unless proven otherwise. The ability to judge firmness of compartments can be unreliable, and numbness or loss of pulses is a very late finding after which permanent muscle damage has already set in, so clinicians should have a low threshold for measuring compartment pressures if the diagnosis is in doubt. This is especially true among patients with multiple injuries, including head trauma, when physical examination may become less reliable. In such scenarios, insertion of a needle into the leg compartment can directly measure the pressure in the leg compartments.

A special note should be made of external or exercise-induced compartment syndrome of the lower leg, which may occur not as a result of a singular trauma, but as a result of intense chronic repetitive use. For example, an individual who runs a marathon with inadequate training may cause such muscle damage and swelling that a compartment syndrome develops.

Imaging and Investigations

There are no specific imaging studies that will diagnose compartment syndrome, although x-rays may show a fracture that could possibly result in causing a compartment syndrome. The diagnosis is made by clinical examination and by directly measuring the compartment pressures if the diagnosis is suspected or in doubt.

Treatment of a Lower Leg Compartment Syndrome

If compartment syndrome of the lower leg is diagnosed or is clinically suspected, the treatment is surgical release of the fascia of the leg. This involves surgically incising the constricting compartments confining the muscles, thereby releasing the pressure in the compartments. The muscles will then bulge out. Any muscle that does not appear to be healthy is removed. After releasing the tight fascia the muscles and nerves begin to receive adequate oxygenated blood to keep the tissue alive, presuming it has not already died during the initial compressive episode.

This type of surgery is done on an urgent basis. Often after surgery, it may not be possible to close the incisions because of the excessive swelling. Sterile dressings can be applied to the wounds and patients often need to return to the operating room later for removal of more muscle, wound closure, or a skin graft procedure.

The exception to an urgent compartment release for compartment syndrome is if the condition has been present for a long period of time, especially longer than 24 hours. Once the muscle has died, releasing the compartment will not bring it back to life, and exposing dead muscle can lead to infection and a high rate of amputation. These scenarios of prolonged compartment syndrome entail complex decisions that are clinically challenging, especially because it is not always clear when the compartment syndrome started, and are best handled by someone well versed in treating the condition.

Sequela of compartment syndrome

If a compartment syndrome occurs and there is muscle death, the tissues in this area will be permanently damaged. In the lower leg, this may mean that the leg becomes weak or, if enough muscle dies, the ankle may not move up and down or in and out. Over time the position of the foot may change making it harder to walk. Furthermore, nerve damage may lead not only to numbness but also chronic pain that can be severe and disabling. Because of the severe consequences of a missed compartment syndrome, surgeons are generally trained to have a very high suspicion for the compartment syndrome and to have a low threshold for measuring compartment pressures and release the compartments if the condition is suspected.

Edited by Stephen Pinney MD, October 15th, 2025. Previously edited by Daniel Guss, MD, MBA, Mark Perry MD and Hossein Pakzad MD