Ankle Fracture Surgery

Indications

Ankle fracture surgery is indicated for patients who suffer a displaced unstable ankle fracture involving either the bone on the inside of the ankle (the medial malleolus), the bone on the outside of the ankle (the lateral malleolus which is also known as the fibula), or both. The procedure is often described as an ankle fracture open reduction internal fixation (ORIF).

The ankle is not a joint that tolerates any displacement as this will lead to uneven loading of the ankle joint, and the subsequent development of ankle arthritis (loss of joint cartilage) in a short period of time. If an ankle fracture has created a displaced or unstable ankle joint, (Figure 1) then surgery is indicated for most patients (some high-risk patients may not be surgical candidates). If the ankle fracture causes the lower bone of the ankle joint (talus) to be displaced by 1 millimeter or more the joint surface of the ankle will be “mismatched” and ankle arthritis will tend to develop over time.

Syndesmosis Injury

One injury that may occur as part of an unstable an ankle fracture is a disruption of the strong fibrous ligaments that hold the two bones of the lower leg together near the ankle joint (fibula and tibia). This is a disruption of the syndesmosis (tibiofibular syndesmosis). If the syndesmosis is disrupted, then the ankle joint will be unstable and surgery is usually indicated.

Procedures

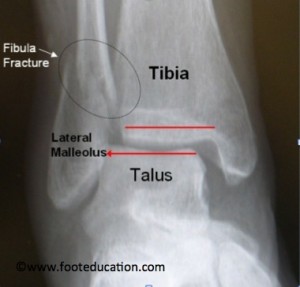

Lateral Malleolus Fracture (Distal Fibula Fracture)

A displaced lateral malleolus (distal fibular) ankle fracture is the most common type of ankle fracture to require surgery. To fix a fracture on the outside of the ankle, (lateral malleolus fracture) an incision is made on the outside of the ankle, essentially along the line of the prominent bone on the outside of the ankle (the fibula). The soft-tissues (tendons, muscles, ligaments) are dissected down to the fracture site. The fracture itself is cleaned up (ex. clotted blood is removed) and the bones are put back together, hopefully in the exact position (anatomic alignment) that they were in prior to the fracture. Once repositioned (reduced) there are a variety of ways to fix (stabilize) the bones. The most common method is putting a screw across the fracture site for compression. This is followed by a metal plate with a series of screws to hold the fibula in its position (Figure 2).

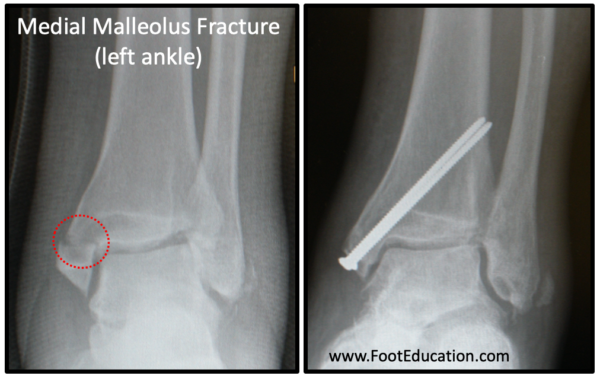

Medial Malleolus Fracture

A fracture of the bone on the inside of the ankle (medial malleolus) is approached through an incision on the inside of the ankle. A vertical incision is made and the surgeon dissects down to the fracture site. The fracture is cleaned up, which includes removal of any clotted blood (hematoma) from around the fracture site. Once prepared, the fracture fragments are put back into position with the aim of positioning the bone fragments in the exact position that they were in prior to the fracture. Once positioned the fracture is usually secured with two screws (Figure 3).

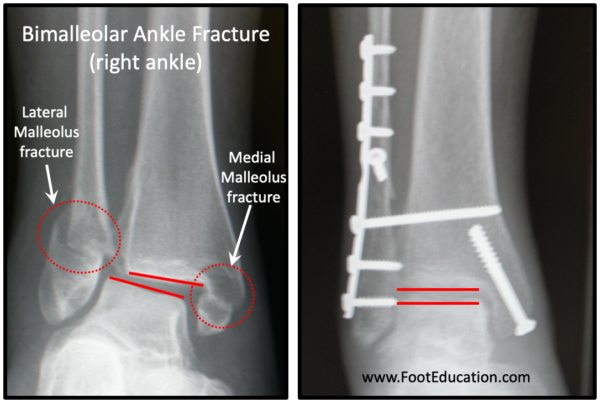

Bimalleolar Fracture

The procedure to stabilize a bimalleolar ankle fracture involves surgical treatment of both a fractured medial malleolus and lateral malleolus. These two procedures are done separately (two different incisions) but are performed together under the same anesthetic. Like each individual procedure, the goal is to reduce the fractures into the position that they were in prior to the fracture and to ensure that the ankle joint itself is perfectly positioned (anatomically reduced) and stable (Figure 4).

Trimalleolar Fracture

Surgery to fix a trimalleolar ankle fracture is similar to that used to fix a bimalleolar ankle fracture, except it also involves a fracture fragment (posterior malleolus) in the back aspect of the tibia. If this posterior fragment is relatively small and does not cause the joint to be unstable then it may not need to be fixed, In this case the fracture is treated just like a bimalleolar fracture. However, if the fracture at the back of the ankle is greater than 20% of the joint surface or leads the ankle joint to be unstable then this posterior fracture fragment needs to be repositioned and fixed. Reducing and stabilizing this posterior malleolus fracture fragment can sometimes be performed percutaneous (through the skin using only tiny incisions). However, often it require making an incision near the back outside aspect of the ankle in order to reposition (reduce) the fracture. Once reduced, this posterior malleolus fracture is usually fixed with screws or a plate and screws.

Intra-articular injury

When an ankle fracture occurs, it is not only the bones that are injured. The surrounding structures are also often injured. These structures can include nearby tendons, ligaments, joint cartilage, muscles, or even nerves. Injury to these other structures can vary from minor to permanent. The smooth gliding articular cartilage within the ankle joint is one of these structures that can be injured in an ankle fracture. This is why surgeons will often look inside the ankle joint when they are fixing an unstable ankle fracture. If the injury to the joint cartilage is bad enough following an ankle fracture it can lead to ankle arthritis.

Stabilizing a Syndesmotic Injury/Disruption

If the strong fibrous tissues holding the tibia and fibula together (tibiofibular syndesmosis) is injured (partially torn) or completely disrupted, it should be repaired. A syndesmotic injury can occur with a fracture of the fibula far away from the ankle joint or without any fracture at all. The surgeon will often assess the stability of the syndesmosis, either before or during surgery, by “stressing” the ankle under fluoroscopy (a portable x-ray) or performing weight-bearing x-rays (if this is possible) to see if the ankle “opens up” (does the talus shift out of position when stressed). The syndesmosis can sometimes be assessed during an ankle arthroscopy (looking inside the ankle joint with a small camera). If the syndesmosis is determined to be unstable it is stabilized so that it will heal in the desired (reduced) position. The syndesmosis is usually stabilized by placing a strong suture device (or 1-2 screws) across the fibula and into the tibia. This serves to stabilize these bones and allow the syndesmosis to heal. If screws are used after approximately 3-6 months, (once the syndesmosis has healed) the screws are removed.

Recovery

Recovery following ankle fracture surgery varies depending on the extent of the injury, the type of surgery performed, and the preference of the surgeon. The general goal is to get all of the bones to heal AND rehabilitate the soft-tissues (muscles, tendons, ligaments, etc.) so that the strength and flexibility that is lost following the injury is regained. A typical recovery protocol for a common ankle fracture requiring surgery might include:

0-6 weeks Post-Surgery

Patients undergoing a typical ankle fracture surgery will usually need at leas 6 weeks for the bone to heal. During this period, the patient is either in a cast or cast boot and remains non-weight bearing or touch weight-bearing through the heel. If a removable cast boot is used it may be possible to begin gentle range of motions exercises 2-3 weeks after surgery.

6-10 (or 12) weeks Post Surgery

At 6-8 weeks post-operatively x-rays are often taken. If the bones are healing well patients be able to increase weight bearing as tolerated in a protective boot. More active rehabilitation exercises, often including formal physical therapy, is usually started during this period of the recovery.

10 (or 12) weeks + Post Surgery

Patients can begin transitioning into a shoe and continue to rehabilitate at this point. A focus on regaining lost strength, flexibility, and balance (proprioception) is important at this time. It can often take a year or more before a patient has optimized their recovery. Some residual weakness and stiffness is not uncommon.

Potential Complications

Nerve Injury

Injury to the superficial peroneal nerve or the Sural nerve can occur due to the placement of the incisions, specifically for a lateral malleolous fracture. Nerve injury can occur due to retraction, direct injury, or from scarring during the recovery process. If these nerves are injured or cut, the patient could end up with numbness or pain along the path of the nerve (onto the top or outside of the foot).

Atrophy

Due to the lack of movement after the surgery, calf muscles and other muscles in the lower leg have a potential to atrophy. The calf muscles may take a while to strengthen, and may never reach its full pre-surgery strength.

Stiffness

The capsule surrounding the ankle joint may get stiff, which may decrease the range of motion around the ankle joint. Some residual loss of ankle motion is common following ankle fracture surgery.

Painful Hardware

About 10-20% of patients experience pain associated with the screws and plates that are used to secure the bone fragments. These patients will need to undergo removal of the screws due to discomfort, once the bones have healed.

Post-Traumatic Ankle Arthritis

Having an unstable ankle fracture that requires surgery will increase the chances of developing ankle arthritis. Ankle arthritis is about 10 times less common than hip or knee arthritis. Most patients who have an ankle fracture will not develop significant arthritis. However, the majority of the patients who develop significant ankle arthritis have had a major ankle injury in the past.

Failure of Hardware with Syndesmosis

If the syndesmosis is fixed with screws there is the potential for the screws to break at the syndesmosis if they are not taken out early enough. Although it may sound very troubling, the broken screws have no bearing on the patient’s symptoms.

Failure of Syndesmotic Fixation

Rarely, after removal of the syndesmotic screw fixation, an injury may recur if the ligaments have not healed adequately. This may show itself as ongoing pain in the region. Should this happen further surgery may be required.

Venous Thromboembolism (Blood Clotting)

Some patients may be at risk of blood clotting (venous thromboembolism) related to the ankle fracture and post-operative immobilization. This can be in the form of a blood clot in the leg (deep vein thrombosis -DVT) or a blood clot that travels to the lungs (pulmonary embolism). Your surgeon may choose to commence anticoagulation (blood thinning medications) after undertaking a risk assessment of your situation. Those most at risk of venous thromboembolism are those who have had blood clots in the past or who have a first degree family member (mother, father, brother, or sister) who has had a serious blood clot.

Edited December 14th, 2023

Originally edited by Paul Juliano, MD and Peter Stravrou, MD

sp/12.14.23