Peroneal Tendon Transfers

Peroneus Brevis to Longus & Peroneus Longus to Brevis

Edited by Daniel Guss, MD

Indications

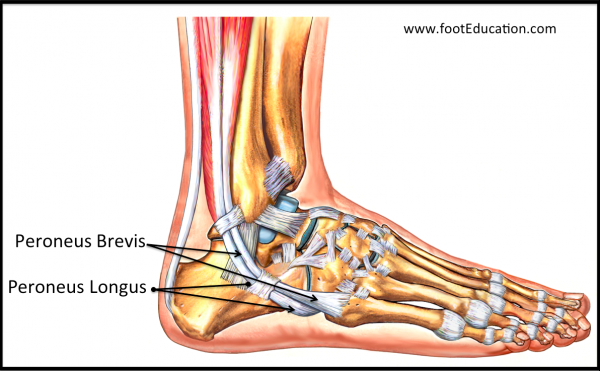

Both of the peroneal tendons serve to move the ankle and foot out to the side (eversion), and to help stabilize the ankle and foot when walking. The peroneus brevis attaches at the base of the midfoot (base of the fifth metatarsal), whereas the peroneus longus tendon runs in a similar direction but then wraps underneath the foot and attaches on undersurface of the inside part of the foot (base of the first metatarsal bone) (Figure 1). Transferring one peroneal tendon to another is often indicated when degenerative changes render one of the two tendons non-salvageable, or in order to optimize their line of pull.

Figure 1: Peroneal Tendons

The most common scenario is one in which the peroneus brevis tendon is transferred to the peroneus longus tendon when tears or degenerative changes to the peroneus brevis tendon are severe enough that the tendon is no longer salvageable. In this procedure, the diseased tendon of the peroneus brevis is excised, often to a level above the ankle joint, and reattached to the healthier peroneus longus so that the both the peroneus longus and peroneus brevis muscle both pull through one tendon. This minimizes the degree of weakening resulting from a tendon excision procedure.

A second less common procedure is the converse, in which the peroneus longus tendon is transferred to the brevis. This is often performed when the peroneus longus muscle is overactive relative to the brevis tendon, causing the base of the great toe to be driven into the ground with each step. This may be seen in an excessively high arched foot. It is common in a condition like Charcot-Marie Tooth, where patients develop a pronounced high arch but lose the ability to forcibly push their ankle outwards. When present, it may lead to pain at the base of the great toe as well as pain on the outside of the ankle. This can usually be managed with orthotics and other non-operative means. However, if non-surgical treatment fails, a peroneus longus to peroneus brevis transfer may be indicated either alone or in combination with other procedures designed to correct the associated deformity.

Procedure

Performing a peroneal tendon transfer procedure involves making an incision on the outside back part of the ankle, and exposing both of the peroneal tendons. The diseased tendon is excised to a healthy level and then the tendon is transferred to its counterpart based on the desired effect as discussed above.

Recovery

To be successful, this procedure needs the tendon transfer to heal solidly. This usually requires a minimum of six weeks of either non-weight bearing or relatively limited weight bearing, with the foot and ankle immobilized in either a cast or a CAM walker boot. After this, the ankle is rehabilitated and the muscles are developed so that they can function in the new manner that they are being used.

Potential Complications

Potential complications that are specific to this procedure include:

- Sural Nerve Injury. An irritation or injury to the sural nerve is relatively common. The nerve runs near the incision and can be stretched, irritated by scar tissue, or even cut. If a sural nerve injury develops, there will be numbness and/or a burning sensation on the outside of the foot.

- Failure of the tendon repair. Tendon failure is also a possibility. If this occurs, there would be limited or weak movement of the foot and ankle to the outside (eversion).

- Tendon Dislocation. In order to work on the peroneal tendons, they must be exposed out of their sheath, which helps stabalize the tendons. This sheath must be repaired and must heal to prevent dislocation of the transferred tendons.

Previously edited by Paul Juliano, MD

Edited August 31, 2018

mf/ 3.19.18