Gastrocnemius Slide

(Strayer Procedure)

Edited by Christopher W. DiGiovanni

Indications

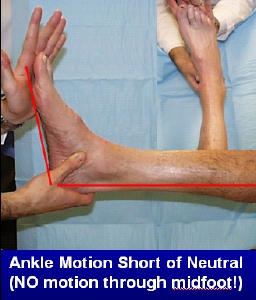

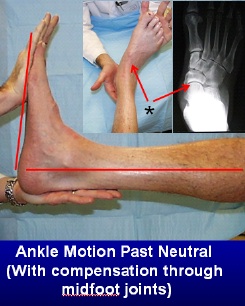

A gastrocnemius recession, or Strayer Procedure, is an operation designed to release the gastrocnemius muscle as a means of restoring it to a more normal anatomical length that promotes healthier gait, stance, and function of the foot and ankle. The procedure is indicated for patients who have only tightness on the outer calf muscle (gastrocnemius) as a cause for their equinus contracture, rather than tightness of both muscles (whereby a full Achilles tendon lengthening would be required to have the same positive clinical effect). Patients who undergo this intervention should have already undergone several months of gastro-soleal (Achilles) stretching exercises and thus failed non-operative management. The presence of this anatomical abnormality can usually be identified on physical exam, as gastrocnemius contracture or “equinus” is generally characterized by an inability to bend the ankle joint past neutral (a right angle position of the foot to the leg) when the knee is straight while being able to restore much of this upward movement when the knee is bent 90 degrees (the so-called Silverskiold maneuver) (Figure 1a & 1b).

Figure 1a: Foot does NOT reach a right angle to the lower leg with the knee straight

Figure 1b: Ankle motion PAST neutral when the knee is bent; note that this can be misinterpreted if compensation is permitted through other adjacent joints in front of the ankle, so the foot must be held in a neutral position during this test at all times.

Procedure

Although there exist a number of described ways to perform a gastrocnemius recession, they all involve sufficient release of the gastrocnemius tendon in order to functionally restore a more normal resting length to the calf muscle as well as a more normal amount of upward motion (dorsiflexion) to the foot during stance and gait. Typically, a small incision is made on the posterior mid aspect of the lower leg to expose the area where this muscle begins to form tendon (Figure 3). Once this anatomic area of the gastrocnemius, called its aponeurosis, is delineated, the tissue is cut across and lengthened to a desired amount that permits better dorsiflexion motion of the foot when it is pushed upward. The released tissue is usually thereafter sutured down to the underlying intact soleus muscle-tendon unit in its new lengthened position so there is then less ultimate tension on the Achilles tendon where these two muscles eventually become “one”. This effectively lengthens the calf muscle, and patients will usually then exhibit the same ankle motion with their knee straight that they previously had only with their knee bent. After the gastrocnemius muscle tissue is lengthened and repaired, the wound is then sutured closed and the leg is placed in a splint or cast to hold the foot and ankle in a neutral position while all of this heals.

Figure 3: Typical location of calf incision (dotted line)

Recovery and Outcome

After the first two weeks of splinting post-surgery, sutures are usually removed and the patient is transitioned into a removable controlled ankle motion (CAM) boot that permits progressive range of motion and weight-bearing through a guided physical therapy program. During this initial 6 week recovery period, it is important that the foot be maintained at a right angle while sleeping so that the tissue heal in proper position, although during the day the patient can be permitted to progressively weight bear and perform range of motion exercises to recondition the limb. These Calf stretching exercises can begin as soon as the sutures are out and the patient is sufficiently comfortable. After the discomfort from surgery has settled, it’s also important to begin progressive restoration of strength in the calf. By roughly 8 weeks post-operatively, most patients can usually walk reasonably normally, although it may take 8-12 months to regain 90-95% of the original calf strength. It should be noted that gastrocnemius recession is often done in conjunction with other procedures that are necessary to treat certain foot or ankle conditions, and if this is the case a patient should logically expect a slower surgical recovery. In general, most patients are back in a pair of sneakers within 6-8 weeks after this procedure, and will typically enjoy significant improvement in their original contracture and related pre-surgical condition(s).

General Complications

Specific Complications

- Skin tethering or scarring: Occasionally, the scar where the incision was made may cause some puckering, keloid formation, or irritation in certain patients. This is relatively unusual, however, although unfortunately it cannot generally be predicted ahead of time.

- Often scar creams and deep massage to this area early in the post-operative period can break up these adhesions.

- Injury/Irritation to the sural nerve: The sural nerve, a small sensory nerve coursing down the lower limb, often runs directly along the gastrocnemius. Although uncommon, this nerve can become stretched, irritated, or even injured as a result of this procedure., which can lead to some degree of pain and/or numbness around the outside of the foot. In most cases, if this occurs it will usually be self-limiting although it can take many months to resolve.

- Calf atrophy or weakness: Some initial calf weakness occurs in all patients. However, it is usually not clinically significant and typically resolves within 9-12 months of surgery. 5-10% of patients, however, develop a noticeable atrophy that persists longer than expected. While this is rarely of any clinical consequence, patients who develop this may find it unattractive.

Edited on May 6, 2018

Previously Edited by Daniel Cuttica, DO

mf/ 5.8.18