Bones and Joints of the Foot and Ankle Overview

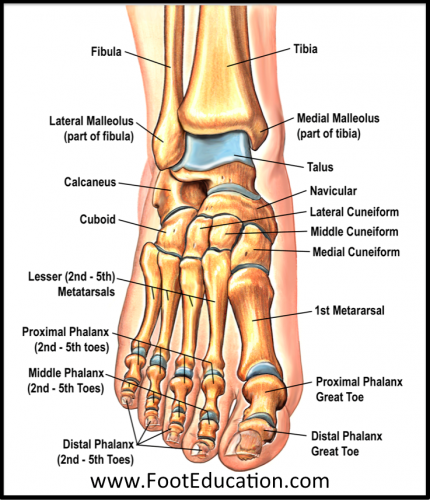

Figure 1: Bones of the Foot and Ankle

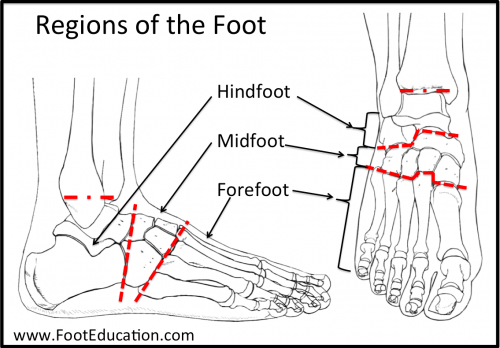

Regions of the foot:

Figure 2: Regions of the Foot

The bones of the foot and the joints of the foot can be more easily remembered and understood if the foot is divided into regions

- Hind-foot – as the name suggests, the hindfoot is the portion of the foot closest to the center of the body. It begins at the ankle joint and stops at the calcaneal-cuboid joint.

- Mid-foot – The midfoot begins with the calcaneal-cuboid joint, and essentially ends where the metatarsals begin. While it has several more joints than the hind-foot, it still possesses little mobility.

- Fore-foot – the forefoot is composed of the metatarsals and phalanges. The bones that comprise the fore-foot are those that are last to leave the ground during walking.

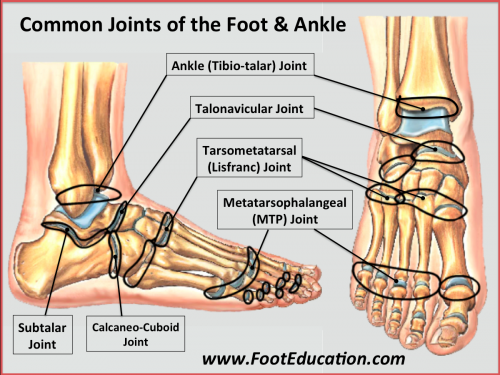

Mobile Joints of the foot and ankle:

There are many joints in the foot. However, in order for the foot to be stable many of these joints do not move much. This is due to strong ligaments that connect these joints and limit their motion. However, for normal biomechanics of the foot there are certain joint that need to move a lot, and some that move a moderate amount. These “mobile” joints are listed below:(See Figure 3.)

- Ankle joint

- Sub-talar joint

- Talo-navicular joint

- Metatarso-phalangeal (MTP) joints.

Joints of the Foot that move a moderate amount:

- Calcaneal-cuboid joint

- Cuboid-metatarsal joint for the fourth and fifth metatarsal.

- Navicular-cuneiform joints

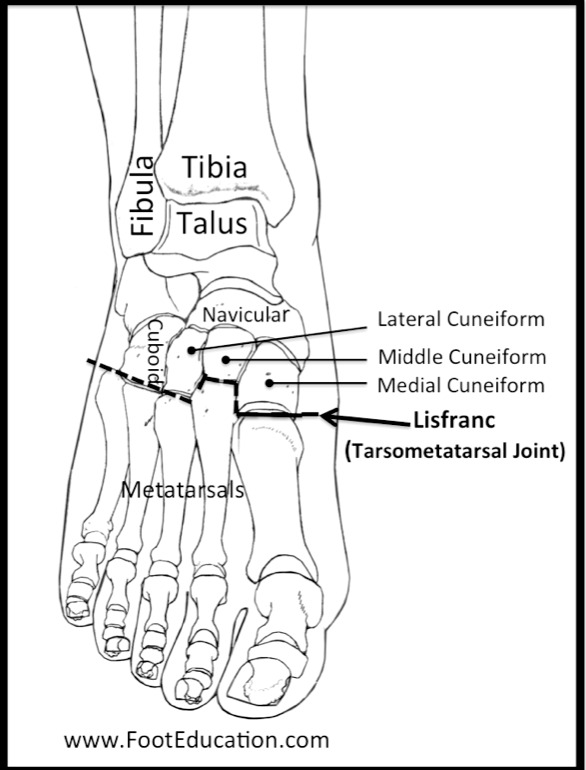

- Joints of midfoot or “Lisfranc” Joint (a.k.a. tarsometatarsal (TMT) joints or cuneiform-metatarsal joints)

Figure 3: Common Joints of the Foot and Ankle

Bones of the lower Leg and Hindfoot: Tibia, Fibula, Talus, Calcaneous.

Tibia and Fibula (Long Bones)

Though the tibia (commonly called the shin bone) is not a part of the foot, it plays an important role in the functioning of the foot and ankle. The foot is connected to the body where the bones of the foot and ankle meet the tibia and fibula (the fibula is the small bone to the outside of the tibia). The tibia is also responsible for holding up 85% of the weight that presses down on the foot in the standing position. The tibia and fibula are held together by a tough layer of connective tissue, known as the interosseous membrane. The interosseous membrane thickens in the lower part of the leg in order to make the ankle more stable. The tibia and fibula form the ankle joint where they connect with the talus. These two bones form a sort of dish which the talus fits into. This dish is known as the mortise of the ankle joint.

Talus

The talus is something of an odd bone because of its strange shape and the fact that 70% of this bone is covered with joint cartilage (hyaline cartilage). The talus acts as a “ball joint” playing the critical roll of connecting the lower leg to the foot. The talus is covered by so much cartilage because it connects so many different bones. The talus holds the ankle together by connecting to the lower leg. It connects to the heel bone (calcaneus) on its underside via the subtalar joint. It also helps to connect the back part of the foot (hindfoot) to the midfoot via the talo-navicular joint. These series of joints allow the foot to rotate smoothly around the talus, as when you roll your ankle in a circle. Unfortunately, the talus has relatively poor blood supply, which means that injuries to this bone take a greater time to heal than might be the case with other bones.

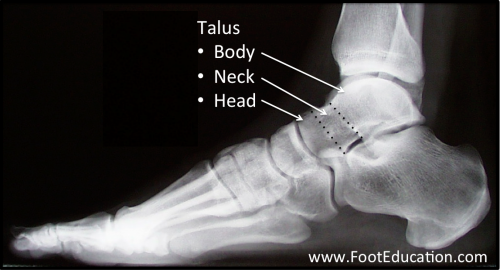

Parts of the Talus

The talus is generally thought of as having three or four parts (Figure 4):

- The talar body including the “dome” of the talus

- The talar neck

- The talar head

The talar body is roughly square in shape and is topped by the dome. It connects the talus to the lower leg at the ankle joint. The talar head interacts with the navicular bone to form the talo-navicular joint. The talar neck is located between the body and head of the talus, and is remarkable because it is one of the few areas of the talus not covered with cartilage, and is one of the few places that blood can flow to in the talus.

Figure 4: Talus Anatomy

Calcaneus (The Heel Bone)

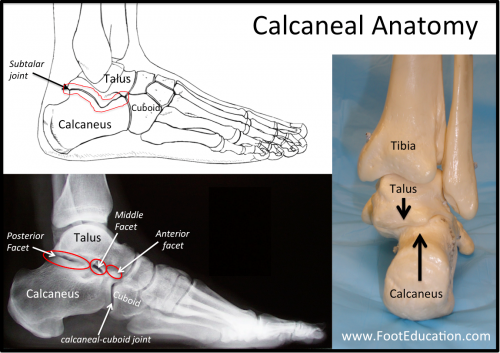

The calcaneus (Figure 5) is commonly referred to as the heel bone. The calcaneus is the largest bone in the foot, and along with the talus, it makes up the area of the foot known as the hind-foot. The calcaneus is something like an oddly shaped egg; hard cortical bone on the outside covers softer cancellous bone on the inside. There are three protrusions on the top surface of the calcaneus (the posterior, middle, and anterior “facets”) that allow the talus to sit on top of the calcaneus, forming the subtalar joint. The calcaneus also joins to another bone at the furthest end, away from the lower leg and toward the toes. At this end, the calcaneus connects to the cuboid bone to form the calcaneocuboid joint.

Figure 5: Calcaneal Anatomy

Subtalar Joint

The talus rests above the calcaneous to form the subtalar joint. However, the talus does not sit directly on top of the calcaneus. Instead, it rests slightly offset toward the outside of the foot (the side nearest the little toe). This positioning allows the foot to cope with uneven terrain because it allows a little more flexibility from side to side. The subtalar joint doesn’t move independently; it moves along with the talo-navicular joint and the calcaneo-cuboid joint, two joints located near the front of the talus.

Bones of the Mid-foot: Cuboid, Navicular, Cuneiform (3)

Figure 6: Bones of the Midfoot

Cuboid

The cuboid bone is one of the main bone of the midfoot. It is a square-shaped bone on the outside of the foot and possesses several places to connect with other bones. The main joint formed with the cuboid is the calcaneocuboid joint. Farther along its length, the cuboid also connects with the base of the fourth and fifth metatarsals (the metatarsals of the last two toes). On the inner side, it also connects with one of the lateral cuneiform bones.

Calcaneo-cuboid Joint

The calcaneocuboid joint attaches the heel bone to the cuboid.

Navicular

The navicular is located in front of the talus and connects with it through the talonavicular joint. The navicular is curved on the surface nearest the ankle. The side farthest from the ankle joint connects to each of the three cuneiform bones. Like the talus, the navicular has a poor blood supply. On the inner side (closest to the middle of the foot), there is a piece of bone that juts out, which is called the navicular tuberosity. This is the site where the posterior tibial tendon anchors into the bone.

Talonavicular Joint

As the name suggests, the talonavicular joint connects the talus to the navicular. The curve of the navicular is designed to connect smoothly with the front surface of the talus. This joint allows for the potential to have significant motion between the hindfoot and the midfoot, depending on the position the hindfoot is in.

Cuneiforms

There are three different cuneiform bones present side-by-side in the midfoot. The one located on the inside of the midfoot is called the medial cuneiform. The middle cuneiform is located centrally in the midfoot, and to the outside is the lateral cuneiform. All three cuneiforms line up in a row and articulate with the navicular, forming the naviculocuneiform joint. The structure of the cuneiforms is similar to a roman arch. Each cuneiform connects to the others in order to form a more stable unit. These bones, along with the strong plantar and dorsal ligaments that connect to them, provide a good deal of stability for the midfoot.

Bones of the Forefoot: Metatarsals (5), Phalanges (14), Sesmoid Bones (2)

Metatarsals

Each foot contains five metatarsals. These are the long bones that lead to the base of each toe. The metatarsals are numbered 1-5, starting on the inside and leading outward (from big toe to smallest). Each metatarsal is a long bone that joins with the mid-foot at its base, a joint called the tarsometatarsal joint, or Lisfranc joint. In general, the first three metatarsals are more rigidly held in place than the last two, although in some individuals there is increased motion associated with the 1st metatarsal where it joins the midfoot (at the 1st tarsometatarsal joint), and this increased motion may predispose them to develop a bunion.

The long part of the metatarsal bone is known as the metatarsal “shaft”, and the thick end of the bone nearest the toes is known as the metatarsal “head” (the metatarsal neck lies between the shaft and head). The head serves two very important functions:

- First, the metatarsal heads are the locations where weightbearing takes place.

- Second, the phalanges connect to the foot at the metatarsal heads at a joint called the metatarsal-phalangeal joint. These joints are very flexible, allowing the metatarsal heads to continuously support the weight of the body, as the foot moves from heel to toe.

First Metatarsal – The largest of the metatarsal, both in terms of length and width.

Second Metatarsal – The fore-foot is made extremely stable not only by the ligaments connecting the bones, but also because the second metatarsal is recessed into the medial cuneiform, in comparison to the others. The second metatarsal may be overly long in some individuals, predisposing them to 2nd metatarsalgia.

Fourth and Fifth Metatarsal – The fourth and fifth metatarsal may have greater range of motion than the others do.

Phalanges

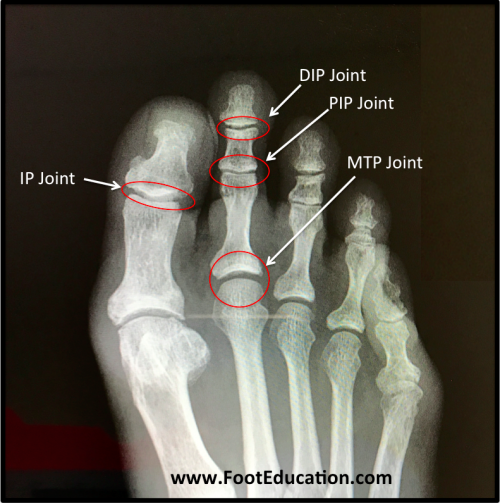

The phalanges make up the bones of the toes. They are connected to the rest of the foot by the metatarsal-phalangeal joint. The first toe, also known as the great toe due to its relatively large size, is the only one to be comprised of only two phalanges. These are known as the proximal phalanx (closest to the ankle) and the distal phalanx (farthest from the ankle).The four “lesser toes” (toes 2-5) all have three phalanges. The phalanx closest to the ankle is known as the proximal phalanx, which articulates with the “middle” phalanx, the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIP joint). The middle phalanx meets the “distal” phalanx at the distal interphalangeal joint. An imbalance in the tendons pulling across these small joints of the toes will lead to deformity of the toe, such as a clawtoe. A list of the joints of the toes can be found below (Figure 7).

- Inter-Phalangeal Joint (great toe only)

- Proximal Inter-Phalangeal Joint (PIP joint – toes 2-5)

- Distal Inter-Phalangeal Joint (DIP joint -toes 2-5)

Figure 7: Joints of the Toes

Sesamoid Bones

A sesamoid bone is a bone that is also part of a tendon. An example of such a bone is the kneecap (patella). In the foot, there are two sesamoid bones, each of which is located directly underneath the first metatarsal head. These sesamoids are part of the flexor hallucis brevis tendon.

Edited April 8th, 2024

sp/4.8.24