Peroneus Longus Overdrive

Summary

Peroneus Longus Overdrive is seen in many individuals and is associated with symptomatic conditions such as chronic ankle instability, peroneal tendonitis, and sesamoiditis. The peroneus longus is one of the two muscle on the outside of the lower leg. This muscle functions to prevent the ankle from rolling inwards -but also serves to drive the inside part of the forefoot downwards. This contributes to creating a high arched foot and producing increased pressure at the base of the great toe.

How does Peroneus Longus Overdrive Effect Foot Function?

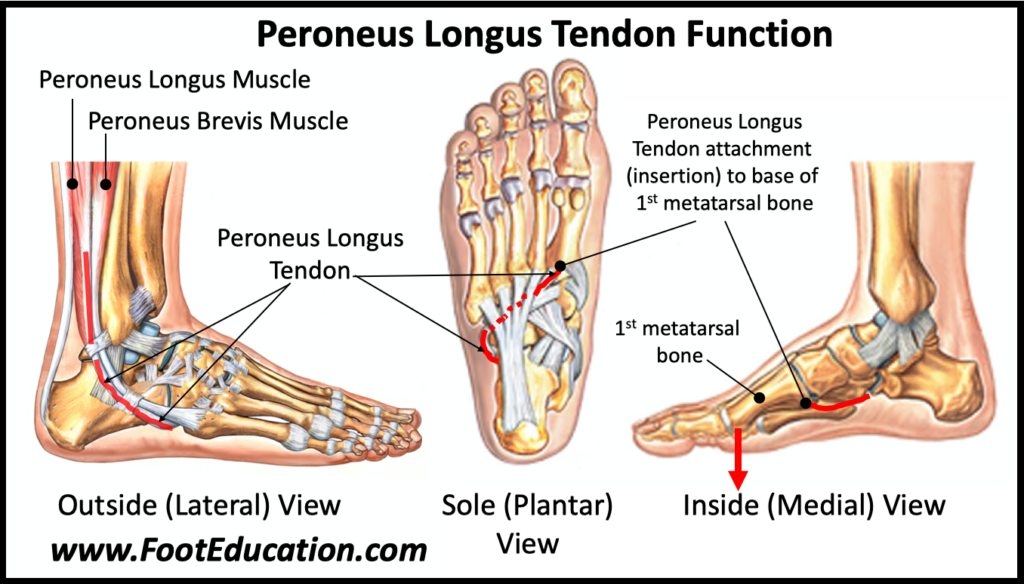

The peroneus longus muscle attaches to the fibula bone on the outside of the lower leg (Figure 1). As the muscle passes on the outside of the ankle it becomes a rope-like tendon. This tendon of the peroneus longus then wraps under the foot before inserting at the base of the bone leading to the great toe (the 1st metatarsal bone). When the peroneus longus muscle contracts while the foot is on the ground it functions to help protect the ankle from rolling inwards and causing an ankle sprain. It also works in synch with the calf muscle to help control the weight of the body as it passes over the foot during walking or running. In addition to these functions because the tendon ends up attaching to the bone at the base of the great toe the peroneus longus also serves to drive this bone downwards.

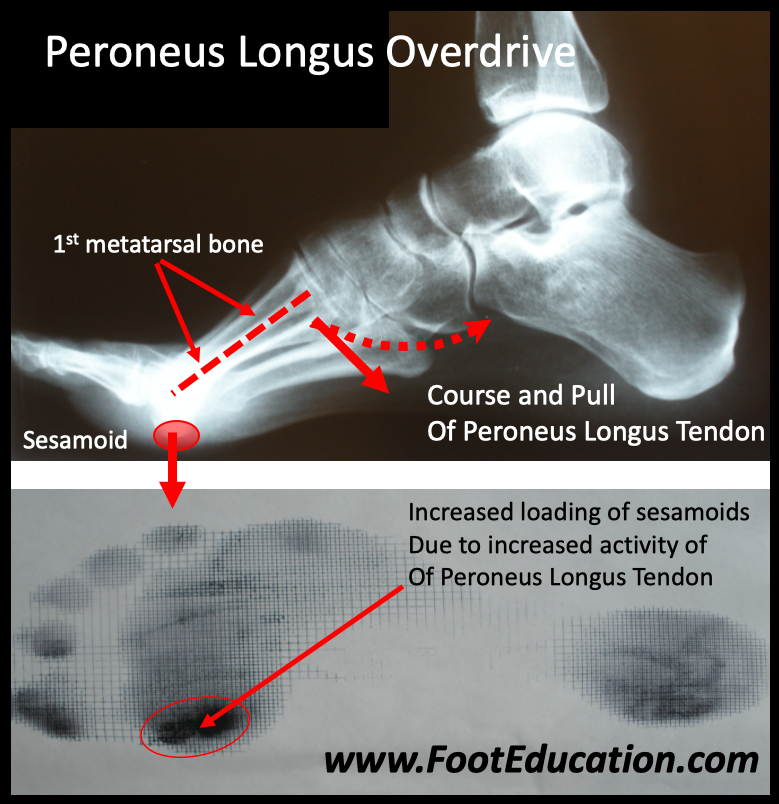

When the first metatarsal bone is flexed downward it creates a “kickstand” effect. This includes creating a higher arch, and forcing the hindfoot into a position where it is slanted inwards (varus position) more than it normally would. A foot with a higher arch and the back part of the foot slanting inwards will cause more traction loading through the outside part of the ankle. This in turn predisposes to the development of peroneal tendonitis, ankle instability, and/or lateral column overload. Peroneus Longus overdrive also creates increased downward pressure at the base of the great toe –as the end of the first metatarsal bone (1st metatarsal head) is driven into the ground (Figure 2). The resulting increased loading over the base of the great toe occurs at the level of the sesamoid bones. The sesamoids are two small bones on the sole of the foot right under the base of the great toe (1st metatarsal head). When the soft tissue and bones in this area get irritated from the repetitive loading this area will become painful in a condition known as sesamoiditis.

An overly strong or active peroneus longus muscle leads to peroneus longus overdrive. Diagnosing this condition can be somewhat subjective. Patients with a high arched foot are more likely to have peroneus longus overdrive. Increased loading over the base of the great toe is also a common finding. A classic sign of peroneus longus overdrive is seen when a patient is asked to point their toes against mild resistance. Normally the foot would point straight down. However, in patients with peroneus longus overdrive the foot will not only point down, but the inside part of the foot, the part where the big toe is, will drive further downwards and rotate outwards. The big toe will also often flex upwards. These findings are signs that the peroneus longus muscle is contracting overly strongly.

Imaging Studies

Peroneus longus overdrive is a dynamic condition so it is not possible to diagnosis it on imaging studies alone. However, certain findings on plain x-rays may suggest that peroneus longus overdrive could be occurring. Weight bearing plain x-rays can be helpful. They will often show evidence of a high arched foot with a plantar flexed first metatarsal. The front view (AP or anteroposterior) view of the foot should also be checked. The two sesamoid bones should be examined as a bipartite sesamoid or even a sesamoid stress fracture may occur more commonly in individuals who have peroneus longus overdrive.

Treatment of Peroneus Longus Overdrive

Most individuals who have an overly strong peroneus longus muscle do not have symptoms and do not need specific treatment. However, if peroneus longus overdrive is associated with a clinical condition such as peroneal tendonitis, chronic ankle instability, lateral column overload, or sesamoidits then that specific condition should be treated. In most instances conservative treatment of these conditions will be successful.

In a small percentage of patients, their symptoms may not be controlled adequately with conservative treatment. In these patients, surgery to address their specific condition may be recommended. For example, patients with ankle instability may benefit from an ankle ligament reconstruction. When surgery is contemplated in patients who have peroneus longus as a driving reason for their condition the surgeon may consider addressing the overly strong pull of the peroneus longus muscle via surgery. This is done by performing a peroneus longus to peroneus brevis tendon transfer. This transfers the pull of the peroneus longus muscle away from the base of the big toe and redirects it to the outside of the foot. The important function of the peroneus longus muscle is retained (limiting inward motion of the ankle and helping the calf muscle), but the excessive downward force on the inside of the foot is removed. This surgery is usually combined with other procedures which often dictates the length of the recovery period. However, if a peroneus longus to peroneus brevis tendon transfer is performed in isolation there is an initial 6-week period where relative immobilization is required to protect the healing tendon. Early range of motion followed by progressive strengthening once the tendon transfer is healed is important and is usually overseen by a physical therapist.

February 29th, 2024